Late last fall, after enduring nearly a full month of mind-numbing quarantine as required by China’s rigorous zero-covid strategy, I finally arrived at the gates of the university where I would be spending the next couple years of my life. The sight of that massive entrance adorned with traditional Chinese dragon statuettes was physical proof that I had survived the gauntlet and come out the other side alive (if not totally sane) and so naturally I was filled with an incredible enthusiasm and optimism for the road ahead, even through it would still be some time before zero-covid was dropped completely. The fact that a group of Chinese and international students were kind enough to meet me at the gate and help with my bags was the icing on a long-awaited cake, so I thought little of it when the first thing one of the Chinese students asked me, a visibly Black American, was whether or not I played for the NBA.

After all, I told myself, I am over six feet tall and on the slimmer side, and this guy didn’t mean anything hurtful or malicious by it, he was just curious and asking an innocent if somewhat silly question, so I shrugged it off. Besides, before I left the U.S. I had spoken with some other Black folks who had lived in China for a while and they let me know that I might run into situations like this every now and then, so it was something I was prepared for, more or less. What I wasn’t prepared for, however, were the very unsettling experiences I’d have around the city once I got out of the campus bubble.

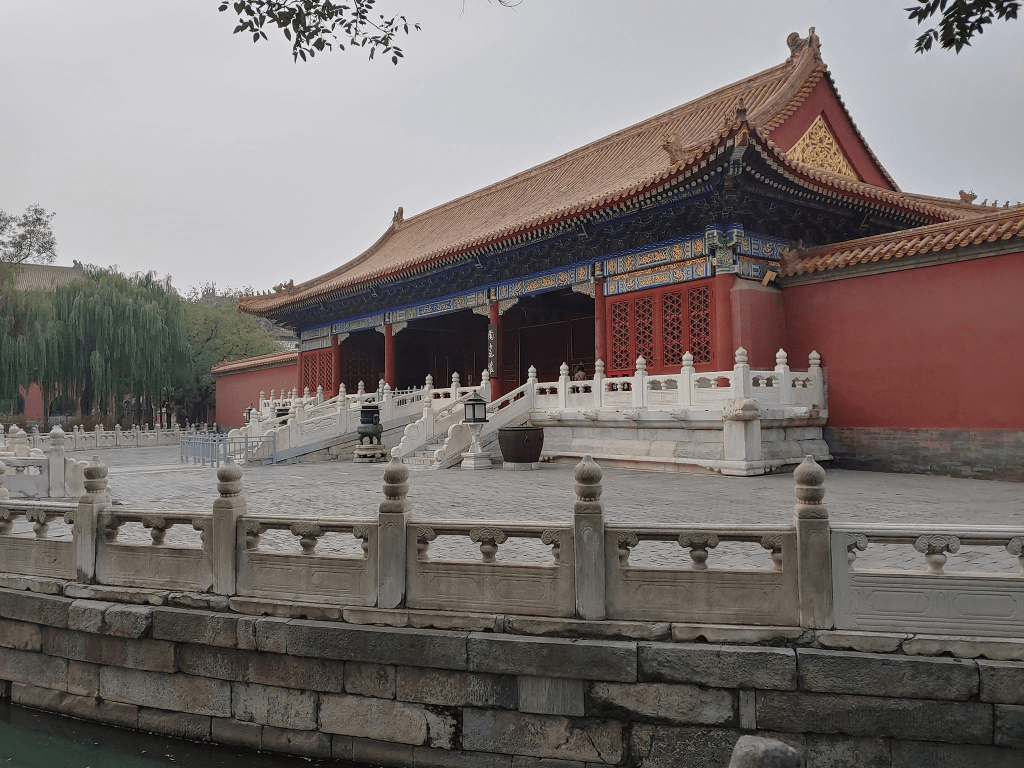

Specifically, no amount of chatting with Black friends or mental preparation could have made me ready for the inevitable and unending stares I’d get from passing Chinese on the streets of Beijing – my skin tone, big lips, and thick afro making it more than obvious that I wasn’t a local. Whether I was going to the clinic, sorting out paperwork at the immigration office, or just going out to explore the city, I was constantly subjected to the glares of passersby ranging from abject confusion to uncensored disgust, making me feel less like a human being a more like a wild animal that had escaped from its enclosure. When I had the privilege to visit the Forbidden City, I was both captivated by the incomparable beauty of that gargantuan compound and deeply disturbed by the constantly piercing eyes of Chinese tourists, as if closely watching me to ensure that I didn’t do anything to disgrace the premises anymore than I already had by simply being there. But despite the stares, I took my pictures, laughed with my newfound Chinese and international friends, and defiantly told myself that I had a great time visiting that veritable marvel of human engineering.

Deep down, however, the experience had seriously shaken me, and one was of the major reasons why I eventually decided to completely shave off my afro completely when I visited Hong Kong later that year, in the hopes that doing so would divert at least some of attention away from me and allow me to exist like a normal human being in this country. On that front, I can report that since my trim I’ve thankfully been getting odd looks less frequently than I did before, but still often enough to remind me that I’m foreigner in an overwhelmingly ethnically homogenous country. It’s also more than a tad ironic that removing one of the most visible signs of my blackness was a prerequisite to being treated semi-normally in a country which claims to champion equality and mutual respect with African countries and asserts that racism is largely a feature of the Western world.

As an Black American, I’m certainly more than aware of my country’s own struggles with the plague of racism, both past and present, as well as its intimate connections with our nation’s progenitors back in Europe. However, as a student of Chinese history, I’m also quite aware of this country’s own sordid legacy of discrimination against the very same Africans it calls “brothers,” not to mention well documented abuses against native minorities like the Tibetans and Uyghurs.

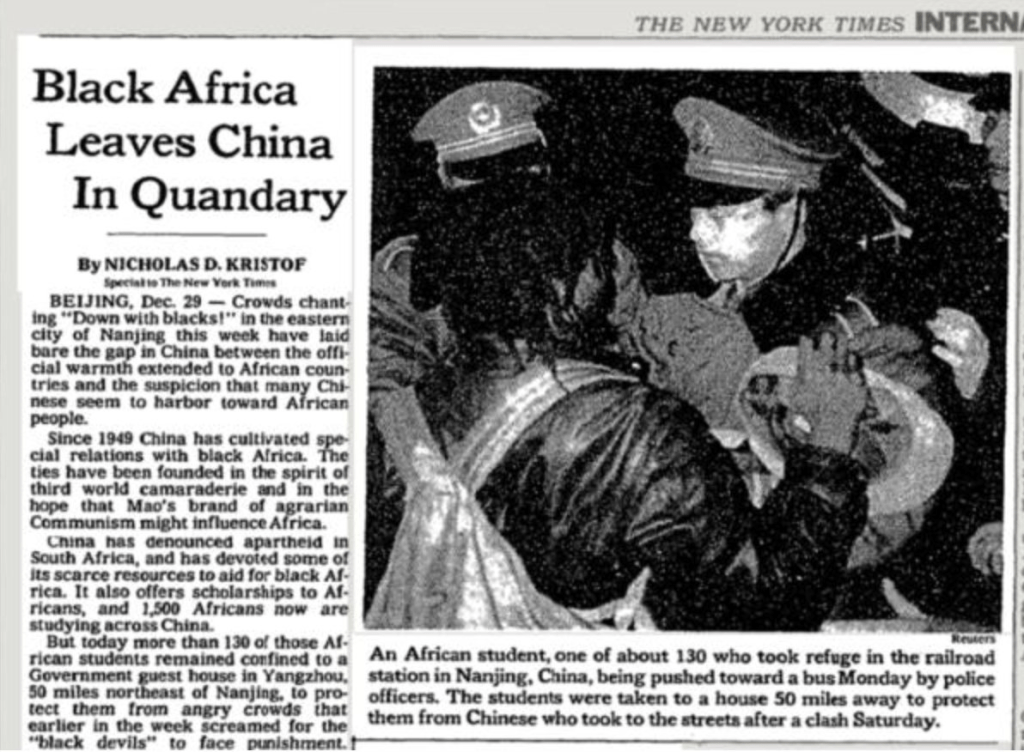

As the China-African specialist Winslow Robertson has cogently summarized, the 1970s and 80s saw a disturbing wave of racist violence and harassment directed against African students studying in China in response to complaints about their “loud music” and unfounded rumors that African men were raping Chinese women. In one particular incident in Shanghai in 1979, as many as 50 foreign students were injured as furious Chinese stormed the international dorms and assaulted their residents with makeshift weapons, and after a similar incident took place in Tianjin in 1986, African diplomats lobbied Beijing to secure better protection for their students but were rebuffed. In 1988, officials constructed a wall around the foreign students’ dorm at Nanjing’s Hehai University and forced them to register all guests so as to prevent Africans from bringing Chinese women to their rooms, and that December, some 300 Chinese students attacked the foreign dorm chanting “kill the black devils!” after rumors began circulating that an African killed a Chinese student. Shortly after the convulsion in January 1989, one young Chinese man was quoted saying of Africans:

“When I look at their black faces, I feel uncomfortable. When I see them with our women, my heart boils.”

The cadres in Beijing certainly talked a big game about global solidarity, but these race riots indicate clearly that many Chinese would have been much more at home at a Klan rally than a struggle session about intersectionality. To China’s credit, these kinds of overt outbursts of racist violence against Black people have become less frequent today, but old prejudices die hard, and contemporary Chinese media is more than willing to play up anti-Black stereotypes. Probably the most egregious example of this is the 2017 blockbuster film Wolf Warrior 2, which takes place in a chaotic unnamed African country currently being ravaged by a bloody civil war with no discernable cause and a malicious pandemic that the locals are helpless to stop. It’s only through the magnanimous aid of China portrayed through the story’s rugged soldier protagonist Leng Feng, a Chinese-funded hospital researching the virus, and a Chinese factory turned safe zone that the infantilized locals are able to survive. As the Malawian writer Beaton Galafa has beautifully argued, Wolf Warrior 2 happily adopts the same anti-African racist stereotypes embodied in the White Savior Complex and Western media like Heart of Darkness and Blood Diamond; reducing the continent and its people to incompetent children in need of a foreign savior at best, and bloodthirsty brutes engaged in mindless violence at worst. Uniquely, however, Wolf Warrior 2 manages to mix all the worst tropes of Hollywood schlock into a single film and was produced with more than $30 million in funding straight from the Communist Party’s Central Propaganda Department, an investment that net over $800 million at the box office and quickly became the highest ever grossing film in China.

More recently, the Covid-19 pandemic saw widespread harassment and discrimination against Africans who were evicted from their homes in Chinese cities like Guangzhou, and 2020’s Lunar New Year gala, the most popular televised event in the country, featured Chinese performers in blackface performing a “traditional” African dance number. A similar event occurred during 2018’s gala, when a Chinese actress in blackface boasting a large fake butt and carrying a basket on her head shouted slogans like “I love China” and “China has done so much for Africa.” In case anyone missed the point, she was paired up with an actor from Cote d’Ivoire wearing a monkey costume. In response to the criticism from abroad that followed, Beijing defiantly refused to apologize, and alleged that any critics had “ulterior motives” for calling out state-sponsored racism. But private Chinese citizens online are just as guilty, frequently tossing around anti-Black racial slurs and demonizing interracial couples for allegedly destroying the Chinese race. In African itself, there’s an entire industry of Chinese expatriate influencers with millions of followers back in the mainland draws that in millions of dollars every year. Some like Cheng Wei in Zambia, rate Black women’s looks and have them dance for videos streamed on Chinese apps like Bilibili and Kuaishou, rewarding the most attractive and entertaining among them with gifts like money, clothes, medicine, and jobs. Meanwhile, Wang Fei in Guinea adopted a local boy who he nicknamed “little monkey,” and taught him how to speak fluent Mandarin and make Chinese food for his YouTube channel with some 255,000 subscribers.

All of this is to show that despite the boisterous rhetoric from the CCP cadres, anti-Black racism is anything but a foreign concept within China – it’s a reality being telegraphed by the government and private citizens for anyone in the world to see, even if they refuse to call it racism. Obviously, not all Chinese people are irredeemably racist or discriminatory towards Black people. I personally have plenty of Chinese friends who treat me with nothing but respect and kindness and whom I know see me no differently because of my race. But that’s the thing about racism – it doesn’t need to be a hegemonic idea shared by every single member of society to be harmful, it just has to be tolerated and downplayed by people who aren’t affected by it. The only way to truly combat racism, be it in China or the U.S. or anywhere else, is to acknowledge and condemn it wherever it’s seen, rather than ignoring it and hiding behind asinine mantras that proclaim only white people can truly be racist.

Leave a comment