This past week I was invited to participate in an all-expenses paid “clean energy study trip” to Jiangsu (江苏) province, cosponsored by the state-owned China Energy Investment Corporation (CEIC, 国家能源投资集团) and the Academy of Contemporary China and World Studies (ACCWS, 当代中国与世界研究院), a foreign-facing public relations institution reporting to the Central Propaganda Department (中宣部) of the Chinese Communist Party. Given the obviously pro-CCP tilt of the sponsors, I was somewhat reluctant to attend the trip, but an environmentalist colleague of mine who had participated in a similar trip several months ago eventually convinced me that the experience would be useful given my focus on climate and sustainability issues, and added that it could be an excellent opportunity to connect with interesting people from around the globe, since my fellow invitees hailed from countries as varied as Russia, the Netherlands, Indonesia, and South Africa, just to name a few.

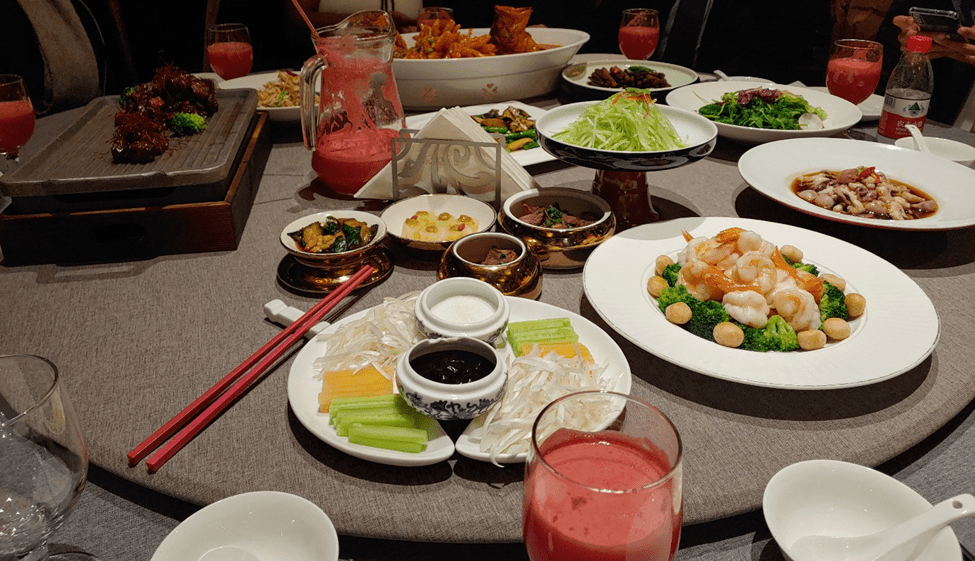

The opening ceremony began Thursday afternoon at CEIC’s national headquarters in Beijing, an imposing glass building reminiscent of the high-rises seen in financial capitals like New York, Hong Kong, and London, accompanied by no shortage of speeches regarding the imperatives of global energy cooperation in this critical time for humanity. In contrast to the hypermodern opening venue, the night ended with a banquet at Hua’s Restaurant, a Beijing staple located in one of the city’s historic siheyuan (四合院) courtyard complexes and whose guest list boasts not only the kings of both Sweden and the Netherlands, but also the prime ministers of Italy, Thailand, and Germany. Clearly the event organizers and their Party superiors decided to spare no expense in making a favorable first impression.

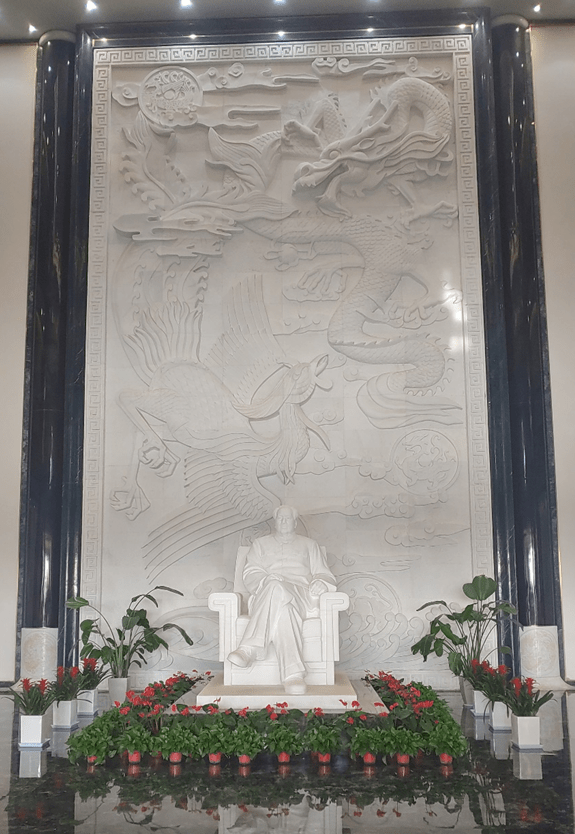

Despite this pampering, however, it was impossible to ignore that the first day of the tour was entirely unrelated to the subject of clean energy, and mostly functioned as an extended photo opportunity for the regional officials and event sponsors to show off the foreigners impressed by their accomplishments. Immediately after landing in Jiangsu, we were whisked away to the city of Taizhou to visit an exhibition center detailing how the city’s development plan had been entirely configured around the healthcare and pharmaceuticals industry, earning it the appropriate if uninspired and bureaucratic moniker of “China’s Medical City.” As soon as we stepped off the bus, we were surrounded by an entourage of cameramen from both national and local state-owned news outlets that would follow us like lost puppies for the remainder of the tour, but for the time being I managed to ditch them by joining the CEIC and ACCWS representatives for the Chinese language version of exhibit, much to their surprise. Our next stop was the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) division of a sprawling state-owned pharmaceutical company, where we were greeted by a massive marble statue of none other than Chairman Mao, who apparently was quite the advocate of TCM in his day.

We wrapped up the night with another speech-laden banquet attended by local Party officials and a leisurely boat ride down the Fengcheng river (凤城河) in Taizhou, which was illuminated by a beautiful display of lights all along its bridges and promenades and punctuated by brief interpretations of Beijing Opera (京剧) by local performers. This little excursion was the only aspect of the first day which could be tangentially connected to the topic of energy, considering that no small amount of it was needed to power the lightshow.

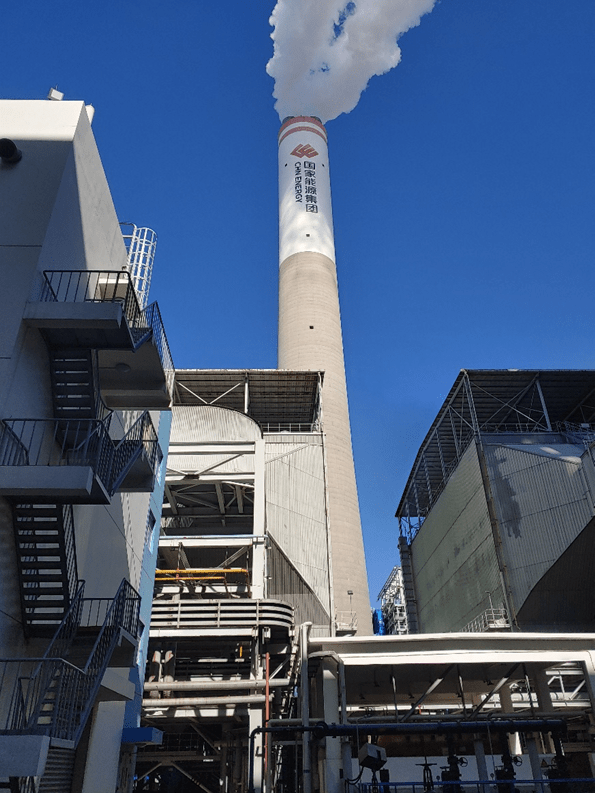

Thankfully, by the second day we finally began to deal with the energy part of the tour in earnest, by visiting a “clean coal” power plant operated by CEIC in Taizhou, again with a small army of cameramen and videographers in tow. Although the term clean coal is often fairly derided as an oxymoron, our sponsors assured us that the innovative carbon capture, usage, and storage (CCUS) system installed in this power plant – the largest such system in China and Asia – allowed it to capture some 90% of the CO2 emitted from its production processes, equivalent to around 500,000 metric tons of the greenhouse gas captured annually. These captured emissions are then stored in massive spherical containers, where they wait to be loaded into special trucks that deliver them to local food, chemical, and industrial facilities for a second life as “recycled” CO2. For instance, the captured emissions can be used to carbonate sodas and other beverages, or to produce organic and inorganic chemical products like silicon and salicylic acid.

At first glance, this sounds all well and good – after all, who wouldn’t want one of the world’s biggest coal consumers to clean up its act? – but the messy details of CCUS complicate the issue considerably. For starters, it’s worth noting that the most vocal backers of CCUS technology are the same fossil fuel companies responsible for emitting so much in the first place, leading many environmentalists to draw the reasonable conclusion that these firms simply see CCUS as a way to keep polluting and raking in huge profits, rather than phasing out fossil fuels. What’s truly damning though, is that many CCUS projects have either failed to get off the ground or only capture negligible amounts of CO2, despite decades of research and billions of dollars in government handouts for their development, making the technology an expensive and time-consuming distraction from solutions readily at hand like renewable energy. Indeed, recent research has estimated that “clean” coal incorporating CCUS technology would be more than double the cost of simply installing wind and solar facilities, not to mention the demonstrated failure of such facilities to deliver on promised emissions reductions. Given these numerous shortcomings and dubious results, I left the facility feeling equally amused and insulted that our sponsors thought it a good idea to include a coal plant on the itinerary of a clean energy tour.

I shouldn’t have been that surprised, however, considering that Beijing’s approach to coal has just as much to do with geopolitics as environmental concerns, especially given its increasingly tense relationship with the US and its allies around the globe. In the wake of Russia’s unprovoked and illegal invasion of Ukraine, officials in Beijing were unnerved by the impact of global sanctions and boycotts against Moscow, likely fearing that they could face a similar fate should they accelerate their aggressive maneuvers in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait, or in an extreme case, attempt to forcibly reunify Taiwan with the mainland. Given this backdrop of geopolitical machinations, President Xi Jinping (习近平) and other high-level officials have repeatedly highlighted the importance of ensuring the nation’s “energy security,” and the abundance of coal within China’s borders makes it an absolutely invaluable resource for achieving that goal.

On the bright side, this preoccupation over energy security also means that China isn’t shying away from massive deployments of renewable energy, as I’ve discussed in previous posts, and our hosts were more than happy to show off this side of China’s energy mix as well. The day after visiting the coal plant, I had the chance to visit one of CEIC’s massive offshore windfarms near the small town of Rudong (如东) to the east. We quite literally got down and dirty on this excursion, riding specially designed sea-tractors onto the seabed and then trudging through the mud to get up close and personal with the massive turbines, where we spoke with several engineers about the project’s development history and even helped some of the workers search for clams buried right under our feet.

After this delightful little field trip, we returned to proper land and entered the windfarm’s monitoring center to receive an overview of how big data was being used to oversee operations throughout the region. In the monitoring center, several massive screens offered readouts on indicators like temperature, humidity, and power generation, while also displaying real-time video footage of all the windfarms under its jurisdiction, including the one we had just visited. Here, we also learned about the environmental impact studies carried out to reduce the windfarm’s impact on local fauna, as well as the countermeasures installed into each turbine to prevent animal injuries, including a high-frequency signal designed to repel incoming birds and an automatic stop function that temporarily deactivates the turbine should the signal fail to deter. Despite all of my criticisms and reservations up till this point, I can say without qualifications that this leg of the tour was an absolutely wonderful experience and left me feeling genuinely informed and impressed at the scale of China’s clean energy development efforts, although it was unfortunate that this was the only real clean energy aspect of the entire tour.

Shortly after this visit, we concluded the tour through a closing ceremony with representatives from CEIC and ACCWS and I made my way back to Beijing. All things considered, I’d say the trip was a worthwhile experience that provided a window into the Chinese energy sector, both highlighting its successes and revealing its contradictions, though I highly doubt the latter was intentional. It also was an informative look into the curious, and at times unsettling Chinese perception of foreigners outside of major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, but that’s a story for another day. Until that day, I’ll leave you with a curious picture I snapped during the tour.

Leave a comment